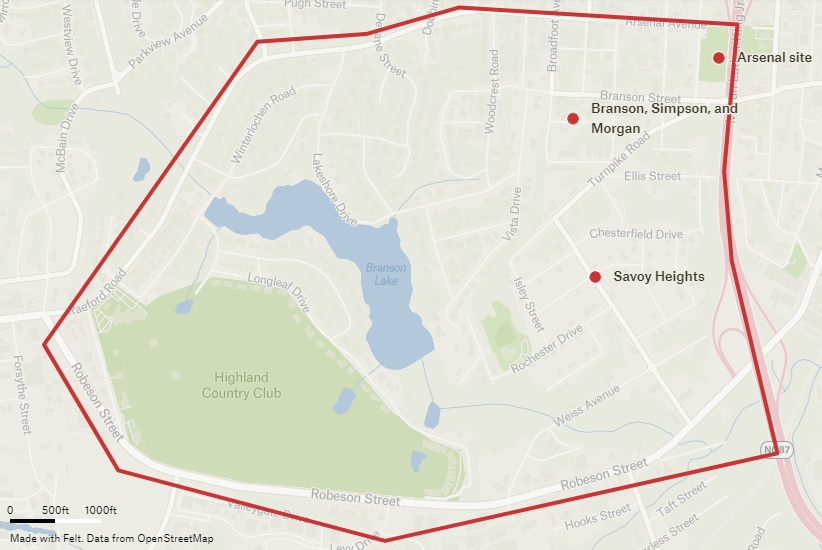

If you’re curious about gentrification in Fayetteville, take a drive down Branson Street and Turnpike Road. The area is at the early-to-mid stages of transformation. Branson runs parallel to Simpson and Morgan Streets, both nearly fully gentrified. Along these three streets, cement trucks, construction crews, and utility vehicles have been common sights. This isn’t totally unexpected, though. Branson, Simpson, and Morgan are just a stone’s throw from the Savoy Heights neighborhood, which is also facing down gentrification. Savoy Heights is bounded on the north by Turnpike Road. North of Turnpike is the Branson area. Now, the average home value in Savoy Heights is $113,313, at least according to Zillow. I expect that will change.

The new development in the Branson area is called “Pineview Manor” and is a Coldwell Banker project. As far as I can tell, the main force behind this gentrification around Branson is the NC History Center on the Civil War, Emancipation & Reconstruction (the name has changed multiple times), being built nearby at the old Federal arsenal. In brief, the arsenal was built by the US government in the years before the Civil War. It was occupied by the Confederacy. Sherman had it destroyed during his brief occupation of Fayetteville in 1865.

Initially controversial due to fears it would become a shrine to the Confederacy, the center faded from public attention due to the pandemic’s impact on construction. I was an early supporter, believing it would offer a truthful narrative, thus breaking with museums that often glorify the Confederacy. I still think that’s true. I don’t doubt the educational value. But, I didn’t expect that this project would drive displacement and gentrification, pushing out the descendants of those it aims to represent. That was naïve of me.

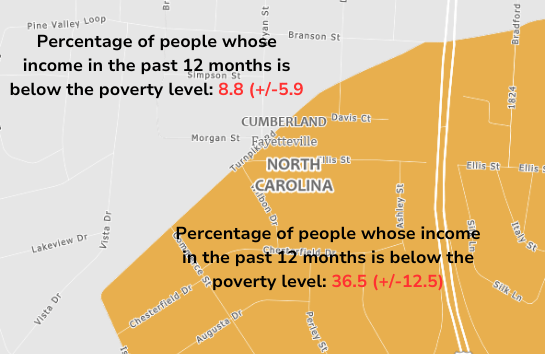

Signs for Kenneth Barefoot of Coldwell Banker abound in the area. As a landless serf myself, I don’t pretend to know much about home ownership but it seems obvious that developers must have known the Center would allow them to move into the area. Like Savoy, the Branson area is predominately African American. If Savoy Heights is successfully gentrified along with Branson, there would be an uninterrupted zone of upper income wealth and majority whiteness between Raeford and Robeson.

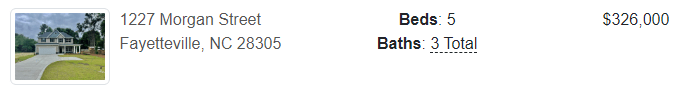

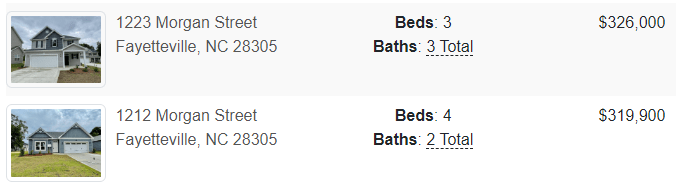

Some of the most recent sales listed by Mr. Barefoot are in the Branson area:

Many of these new homes were built on empty lots, and it was only a matter of time before a developer came into the area. Older homes in the area have been vacated throughout the period of gentrification: some have been gutted and renovated for renting while others appear only to be waiting for demolition.

The image below shows prices on the northern side of Simpson Street. Starting at left, the first six homes were all built in 2022 (numbers 1214 to 1202 respectively). Homes 1112 to 1106 were built in the 1930s-40s. Though the 2023 satellite view doesn’t show it, 1102 Simpson is now occupied by a new home.

I live close to the Branson area, and I’ve run and cycled through there often over the years. Watching the transformation has been disheartening. After all, as values go up in this area, so too do the taxes. Values rising here will entice landlords to raise rents and this effect will bleed over to where I live. Free school lunches will disappear as more well-to-do families move into the area. As a renter, I’m at the mercy of these market forces. I’m lucky enough at the moment to be on a two-year lease, but I dread the renewal process once those two years have ended.

I owe an apology to the people who live in this area. After all, my position is not much more secure than theirs. An increase in rent of even $100 would make living here untenable in the long run. But in my desire to see an educational experience that truly confronts the entire era of the Civil War, I lost sight of the material reality that comes along with this kind of project.

I used to tell people that Fayetteville was immune to gentrification by virtue of being a military town, assuming that the transient nature of the Army would protect the city from becoming a garish assortment of cookie-cutter homes like Cary or Apex. The fact that most outsiders perceive the city as unappealing only strengthened that notion.

I was wrong, though admitting it now does no one any good. I’m sure Kenneth Barefoot, whose name and face I’ve come to know so well, was aware of the potential for gentrification long before I was. Every now and then, I see evidence of another eviction: a mass of furniture, toys, clothes, and groceries dumped in a front yard.

Mr. Barefoot is very good at his job. If I had a home to sell, I’m sure I’d want his help. But the irony here, if you didn’t catch it before, is very clear:

This museum is dedicated to addressing not only the legacy of slavery but also the critical events that unfolded after the Civil War. These include the enfranchisement—and subsequent disenfranchisement—of African American men, particularly during the Reconstruction era. The failure of Reconstruction in the South laid the groundwork for Jim Crow laws, redlining, and other discriminatory practices. Perhaps most notably, it undermined the potential of the “fusion politics” movement in North Carolina during the 1890s. This movement, a rare and powerful alliance across racial lines of Republicans and Populists, was formed to challenge Democratic (and by extension white supremacist) dominance in the state. It garnered strong support from farmers of all races and led to the election or appointment of over 1,000 African American men to various offices. While not a socialist movement (which is a bummer), this broad coalition was highly effective until the Democrats regained control by stoking fears of “negro domination.” For more on this topic, see NCPedia.

The changes happening around Branson Street highlight the complex dynamics of gentrification, where economic pressures often overshadow racial motivations, if racial motivations are even at play. While discussions about race and segregation are essential, it’s crucial to also recognize the broader class implications. Homeowners and renters from all walks of life face the same risk of displacement as housing costs rise, driven by market forces and the pursuit of profit. Gentrification, at its core, reflects a growing divide between economic interests and the well-being of local communities.

As long as housing is viewed as a commodity these issues will continue. Housing is a human right. The Earth is equally ours, we are all born equally cold and shocked by sudden reality. It’s going to be a long, long time before the Sun finally expands enough to engulf our little rock and devours humanity (if we don’t run out of water first). So, let’s unfuck housing and destroy capitalism in the process.