Foreshadowing

By late September, I was nearly certain Donald Trump would win the election. The signs were everywhere, figuratively and literally—even in unexpected places like the Long March for Unity and Justice, a grassroots initiative aimed at going on the record against the rising tide of hatred that made Trump’s return seem inevitable. Indeed, this piece is simply my way of going on record, if only for the sake of my sanity.

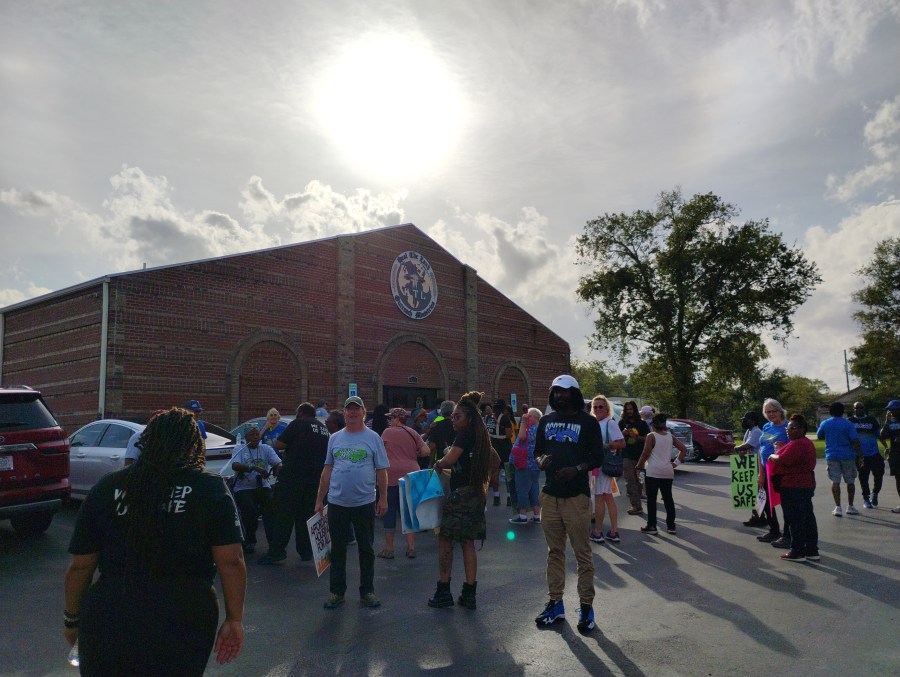

Organized by the Beloved Community Center of Greensboro, the march wound its way through North Carolina, beginning in Cullowhee and ending in Wilmington, cutting through the aftermath of Hurricane Helene as it swept across the state. When the march reached Fayetteville, the skies had begun to clear, but water still pooled around us as we set out.

The marchers that day embodied the coalition we aspired to build—an intergenerational group led by long-time social justice advocates and joined by people of many backgrounds. Predominantly Black, the group included women, LGBTQ+ activists, and others who have tirelessly worked to create a more just community in this city.

Our purpose was to network, to engage in coalition-building that would transcend the outcome of November’s election. No police were present to direct traffic or provide ostensible protection. Instead, the march relied on its own yellow-vested road guards and a cadre of younger people who formed a safety cordon around the group.

“We keep us safe” became both a refrain and an admission of truth. We have no choice but to keep ourselves safe. The Beloved Community Center knows that better than anyone, having its genesis in the Greensboro Massacre of 1979—when Klansmen attacked an anti-racist gathering, aided, at the very least, by local police.

Hay Street and the Market House

We marched from City Hall along Hay Street, once a site of segregation and later a haunt for soldiers bound for Vietnam. Today, it’s “bougie,” with luxury apartments towering above doorways where the unhoused sleep.

We paused at the Market House, a major city landmark. From 1829 to 1865, at least 110 enslaved people were sold or rented there as part of estate sales or other business. During the protests following George Floyd’s murder, one man attempted to burn down the Market House, sparking a wave of racist hysteria on social media. False claims of marauding Black youth were soon being posted to neighborhood groups on Facebook. These false claims elicited lurid, giddy home defense fantasies in the comments.

Efforts to “repurpose” the Market House have been mired in bureaucracy ever since the fire. Committees form and dissolve, leaving the building’s legacy in limbo. It’s a reminder of how absurd it was for anyone in 2020 to claim that the nation was experiencing a “reckoning” with racism. The Market House remains without any definite purpose, a unique piece of architecture trapped inside a traffic circle.

That historical violence—unresolved and unacknowledged—was echoed in the hostility we faced as we turned south, away from the Market House.

Victim and Victor

On Gillespie Street, a white man slowed his truck, leaned out, and began shouting. His face twisted in rage—red, contorted, a whirlpool of fury. Briefly, I recalled a vague online threat of a “hit and run” targeting our march. But this didn’t seem premeditated.

In her poem “In Charlottesville After Charlottesville,” poet Courtney Kampa describes the white supremacists that day:

“…arms roaring / with blood, their faces doing that angry Goya thing / with the colors.”

Goya’s paintings capture something primal and beast-like—Saturn devouring his son, or the mob in The Pilgrimage to San Isidro, their mouths agape in thrilled lunacy. These works symbolize unrestrained, collective rage or abandonment.

The man in the truck embodied this Goya-like frenzy, his fury sparked by the sight of people of color engaged in protest.

Growing up in the 90s, I only saw those kinds of faces in textbooks. The contorted faces of the white mob that followed Elizabeth Eckford in Little Rock, Arkansas, sunglasses and books her only protection. Sneering and triumphant faces, aping for the camera after beating Freedom Riders or carrying out a lynching. Now, I see these faces more and more, and closer.

The same unhinged fear and rage that stormed into Congress, declaring itself the victim and victor, the center of every story. The same calculated and carefully crafted narrative of grievance, victimhood, nationalism, and nativism will be taking over the executive branch on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, January 20, 2025, this time fully endorsed by the electorate – and, in a personal note, two days before my 40th birthday.

Despair in the Face of Crisis

I had a feverish hope at the outset of the pandemic, buoyed by the uprisings that summer, that something good might come out of the horrors of the virus and instability. Something new. That hope was misguided.

When Americans saw that the medically vulnerable, essential workers, and people of color bore most of the suffering, patience for public health measures vanished.

In August 2021, I began to spiral into a depression from which I have not recovered, and likely never will. It was directly tied to the way people reacted—or didn’t react—to the pandemic.

In light of all this, every day is a choice. Continuing to live is a daily choice I have to make.

I choose life not out of some bright-eyed defiance but out of love. For my wife and son, for my community. It is an acknowledgement that I am responsible for more than just myself. I choose life despite the absolute mockery we make of human life and our lives together.

Because we do live together. It’s unnerving to know I’m surrounded by emboldened racists, transphobes, homophobes, and misogynists, yes—but maybe even more unnerving to know I’m surrounded by people indifferent to that fact. Or who think it’s the price of “fixing” inflation. Or who prefer not to think about it at all.

But indifference is also a choice, and the indifferent will bear blame for the atrocities we’ve been promised. It is the indifferent who make it possible for a fascist movement like Trumpism to succeed.

Trumpism is Fascism

With a failed businessman turned reality TV star as its figurehead, Trumpism is a distinctly American fascist movement. Saying so should not be in the least controversial. The parallels are undeniable:

- Nativism and nationalism

- Grievance and victimhood

- Authoritarianism

Fascism thrives on all of these, and the cult of personality around Trump, especially after his felony convictions and survival of an assassination attempt, has only grown. Traveling through rural North Carolina, I’ve seen the countryside transformed, littered with fascist paraphernalia.

Outside Carthage, NC, a grotesque diorama stands—a larger-than-life Trump statue, surrounded by streamers and banners, permanently waving to passing traffic. It might be laughable if not for Trump’s lies, like claiming Haitian immigrants ate citizens’ pets in Springfield, Ohio—a falsehood linked to bomb threats and Proud Boys activity. Trump has pledged mass deportations from Springfield.

Something very wrong is happening—and is about to happen.

But I know some of his supporters who say: “It will be ok.” “He’s not that bad.” “You didn’t die last time!”

This dismisses a crucial truth: the election legitimized the hatred we witnessed on Gillespie Street. It legitimized January 6, 2021, xenophobia, misogyny, bigotry, bizarre conspiracy theories, and the most vile impulses of American id. It legitimized, with the popular vote, a tried and true American neurosis: fear and hatred of immigrants.

Immigrant as Enemy

Trump’s first speech of the 2016 campaign singled out immigrants as a threat to America. Xenophobia has been the bedrock of his movement ever since. His rhetoric and policies toward immigrants are perfectly illustrative of fascism. They are the designated scapegoat, and will bear the brunt of the abuse.

And it is not just the Department of Homeland Security that will carry out the promised cruelty of mass deportation. Militias, which have in the past been broadly antagonistic toward the federal government, are now eager to serve in mass deportation because, of course, they see their ideologies represented in the weird Christian-nationalist fascism of Trumpism.

Now, any American with a firearm and enough sense of grievance can be electrified by rhetoric of war—words like invasion, infestation, replacement. Before the Tree of Life Synagogue attack, Trump and Fox News relentlessly invoked a “migrant invasion,” knowing its violent implications. Words and violence are inseparable, yet those who stoke them feign innocence.

As poet Mary Oliver wrote: “Everyone knows the great energies running amok cast terrible shadows… each of the so-called senseless acts has its thread looping back through the world and into a human heart.”

Acts of violence against the marginalized are not senseless or inevitable. They are deliberate choices, and they are meant to sustain injustice. We have to acknowledge the stakes. Immigrants, queer people, and others have always lived with daily danger. But we are entering a new phase of violence, emboldened by crowds demanding “Mass Deportation Now!”—a euphemism for ethnic cleansing, and a project the scale of which would make even Adolph Eichmann balk.

Deporting millions would upend the nation, a logistical and moral catastrophe. To propose, support, or even tolerate such an act is nothing less than evil.

As we face an ascendant fascist movement, it’s important to understand its origins while also preparing to undermine it.

Hope

Hope isn’t just an emotion; it’s a way of thinking and acting. You can lend your time, energy, or skills. Volunteerism and DIY efforts might be all we have, but they’re not nothing. Still, you can’t help if you’re endlessly online, hashtagging your way through a crisis. The days of #resist are over. Milquetoast liberal posturing will not stop the sin of separating families. Norms and institutions cannot be counted upon. We must be more than rhetorical. Why?

Because this is a unique moment.

In the past, opponents of fascism and systemic oppression pinned their hopes on external forces—foreign intervention against the Nazis or federal government action against Jim Crow. Now, bigotry and racism aren’t fringe—they’re mainstream, guiding the policies of the world’s most powerful nation.

No one is coming from elsewhere to save us.

So figure out who you can trust.

Hope is a choice to continue, not alone, but with other people. You have to reach out to other people, even if it hurts, even if it’s scary. Fascism thrives on alienation and isolation, and on despair. Other people need you, even if you’ve not met them yet.

At the Long March, an older woman struggled with the uneven sidewalks and obstacles. A small group formed a cordon around her, with marchers ahead calling out hazards.

Consider this my call back to you, dear reader: things aren’t going to get better or “be fine.”

Choosing to refuse fascism may seem like an easy choice. But when fascism is the status quo, nothing is quite so easy.

Danny Bryck made this clear in his poem, “If You Could Go Back.” Bryck addresses the reader who, with the advantage of hindsight, claims they would have opposed chattel slavery, would have hidden Jews from the Nazis:

“But people then, just like you / Were baffled, had bills / To pay and children they didn’t / Understand and they too / Were so desperate for normalcy / They made anything normal.”

We keep us safe. Your safety is my safety.

What does it truly mean to refuse fascism? How can you avoid complicity when, by the very nature of being an American, you are part of a global system of exploitation? While you can’t do everything, you can do something. Seek it out. Be open to actions that may push you out of your comfort zone. Above all, ask. Don’t be embarrassed to admit you don’t know what to do. Reach out to those directly affected by Trumpism. You’re not a savior, nor should you try to be—but you can serve.

This is not about selflessness. It is about recognizing our connections and duties to those around us. As James Baldwin reminded Angela Davis:

“If we know, and do nothing, we are worse than the murderers hired in our name.. If we know, then we must fight for your life as though it were our own—which it is—and render impassable with our bodies the corridor to the gas chamber. For, if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.”

We keep us safe. No one else will.